Why Seed Saving and Exchange is Essential Permaculture & Community Practice — a How-To with Red Semillas Libres Chile.

By Crystal Allene Cook

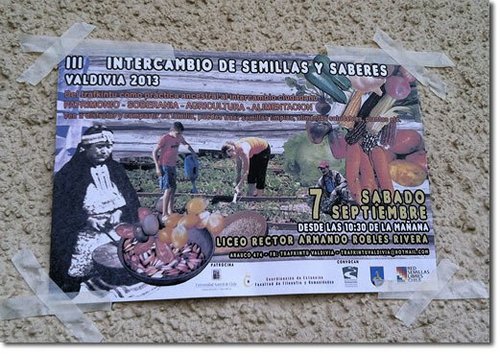

Like many permaculturalists I work another job and this fall mine happened to take me to Valdivia in the Patagonian region of Chile. My first Saturday in town, in the local large supermarket, I spent an hour reading the ingredients of most everything I picked up to buy. I had been feeling a little down about the abundance of chemicals in so much of the food when walking back along a main thoroughfare two large hand-painted signs flapping against a long metal fence caught my attention: Intercambio de Semillas! Plantad y comed semillas libres! “Seed Exchange. Plant and Eat Seeds of Liberty!”

I was stopped in my tracks. Could this be? I hurried over into what seemed to be a school and into a cafeteria full of people hurrying this way and that, setting up for a seed exchange.

Before continuing, I want to say that the organization of this event and the subsequent day’s event (a training in the ethics and practice of seed exchange and seeds as a community bulwark) were so well considered that I have structured this article not only as reportage about the events but also as a How-To in terms of putting on a Seed Exchange, conducting seed exchanges, and using seeds as the basis of community and permaculture practice.

Provide a forum for testimony, education, exchange, and make it fun

At the front of the cafeteria, a mic had been set up and people were coming forward and highlighting the importance of this event, giving shout-outs to people in the room and their regions, and also giving personal and political testimony about the importance of saving and exchanging seeds.

Intermingled with people at tables readying their seeds was a lot of literature about the imperatives for saving seeds, guides on how to save seeds, and guides on kinds of seeds.

After folks had gotten set up an announcer officially started the seed exchange and a few key people were noted. Then, the announcer officially opened the exchange and the sound system switched to festive instrumental music, contributing a party mood.

Though maybe not obvious, but from a pedagogical and community-building perspective this kind of introduction was spot on. The open mic section allowed those already engaged to testify and also educate newcomers. Hearing where people were from opened up the opportunity for more community connection. The testimonies underscore an ethic of seed saving which several speakers noted as a cultural, historical, and human right.

Though maybe not obvious, but from a pedagogical and community-building perspective this kind of introduction was spot on. The open mic section allowed those already engaged to testify and also educate newcomers. Hearing where people were from opened up the opportunity for more community connection. The testimonies underscore an ethic of seed saving which several speakers noted as a cultural, historical, and human right.

Wanting to learn more about the organizers, I approached a moderator and learned about the next day’s event — a training on the ethics and swapping of seeds as community. He pointed me in the direction of a tall woman engaged in discussion at one table and a red-haired man carefully noting information on a packet of seeds for someone else at another table. A fact-finding mission with both of these folks put me on a road outside of Valdivia the next day to learn more.

Lay the conceptual groundwork

In follow-up conversation, I later learned that the tall woman from the day prior, Valentina Vives Granella, settled upon the issue of seed saving, propagation, and exchange as convergent practice that brought together essential human rights as well as a range of issues and concerns (human rights, food, liberty, indigenous rights, economics, etc.). She then became instrumental in forwarding “the seed” through the group Red Semillas Libres Chile, the Chilean Free Seed Network which is, in their words:

… transdisciplinary, not-profit-based, inclusive, horizontally-governed and committed to facilitating the rescue of diverse agricultural practices and cultures, sustained by the convergence of people, intuition , energy and initiatives. We work across the country and base our work in collaboration, diversity, trust, respect and common consent…

For them the seed is not isolated from its larger context nor from its historical role in culture. Seeds contain memory and identity, as their cultivated biodiversity is key for food sovereignty (soberanía alimentaria) and sustainable agriculture practice. Its saving and exchange are the founding sources of agriculture.

In the first part of their seed saving and exchange workshop, Valentina and co-presenter Coloro Magaña laid the ethical groundwork for why this issue has taken center stage in their own regenerative agricultural practices and as a unifying cause.

By contrast, where as much discussion in North America (where I am from) focuses on soil as primary, and while Valentina also pointed out its importance, the seed has become a rallying and practical point of focus in Chile. Many of their points are well-taken, and serve to link agriculture to human culture in ways that people can understand, relate to, and practice.

- The seed is our patron of nature and of agriculture. It contains our depository of the history of a plant and its selection. Seeds are not only “seeds” but contain a context at the local and global levels. The seed is socioeconomic, sociological, and cultural. In fact, more than any other force in terms of providing life on land, it is the most densely powerful force on Earth, in that it goes from something so small into something so many times larger. It supports diversity and contains genetic memory, along with functioning as a living memory of the creativity of past societies. In this, it is more than a mere genetic carrier. In the case of cultivation, we could conceive of it as half genetic and half cultural. In the seed, history, ancestry, and technology converge.

- We have lost our understanding of the stages of the seed. Many of us today would not recognize the stage at which to save a seed. We no longer recognize edible plants at all their stages of the lifecycle and only recognize the product that comes to our table. If we retain the knowledge of seed gathering and saving, we begin the steps to alleviate fear of hunger, as we then possess something powerful to cultivate.

- Seeds are a key practice of liberty. If we don’t have access to the legal means or the knowledge to save seeds, if we lose this right and this knowledge, then we become slaves to those who control the food system. We will also suffer this loss in history and culture.

- Be responsible for starting your own seed banks, don’t rely upon the institutional ones. A seed bank should be a living thing in the hands of the people. You shouldn’t have to register your seed with any government or company. Conserving seeds is a human right, especially the right of peasants and farmers.

- Seeds should be used, not just stored. They are living things, not static. The same happens with culture that’s alive. People are living beings, part of dynamic systems — not museums parts, but memory and heredity that changes, adapts and evolves in time.

- Seed preservation and exchange is a human right, along with clean water and clean soil. Without these three, life fails. Without these three, we become beholden to whoever can provide access. Thus, we lose a right to economic and social self-determination and we lose our communities, and thus we lose autonomy.

- Seeds should not be patented. See number 6. Further, those who seek to do this are interested in food production, as in its production through factory-like processes of speed, mechanization, large-scale, etc., rather than agriculture — with the stress here being on the culture of food cultivation. Those who alter the basic DNA of plants in order to control access to plants are making it to where other people can no longer modify the traits of a seed through traditional means of local adaptation, etc. We cannot ignore the work of the farmer to diversify arable biodiversity and its maintenance and fortification over time. Patent laws seek to promote industrial agriculture at the expense of small scale or traditional agriculture.

- In our contemporary context, hunger is a political, not an agricultural problem. Thus, introducing genetically modified mono-crops will also not solve hunger. Giving people or local farmers access to seeds, clean water and clean soil are the first steps in a country for economic independence or food independence, rather than dependence.

- The consumer must ask questions regarding seed propagation and cultivation. Consumers should connect with local producers and know not only about the chemicals and organic history, but also the history of the seed cultivated. Ask questions such as, how many generations have you been planting this seed? Where did the seed for this come from? How long have you been growing it?

- Follow the model of a Food Constitution or Manifesto. We do not need to register seeds. We do not need governmental validation or regulation of our open-pollinated seeds. Seeds should be up for exchange freely rather than controlled by “free market” laws. We need to stop the introduction of GMOs and chemical substances (agrotoxins) because bees are dying, the soil is dying, biodiversity is suffering, and people are getting sick.

- If you cultivate and exchange seeds, you must pair this with education. It is not enough just to host an exchange, you must educate about why this is important to liberty, culture, history, society, etc.

- Seeds are on a different timetable from us. Just because our society has sped up does not mean seeds must also match our hectic pace. Focus on observation of their patterns and working with nature and the conditions of your climate.

- Every seed is important, not only those for eating or maintaining human health but also those of trees and flowers are vital to maintaining ecosystems.

Demonstrate, Educate, Propagate, Disseminate, Re-congregate!

After a long potluck lunch, we reconvened for the practicum session of the workshop. Coloro, who lives at a permaculture site near Valparaiso (you can see the great work of that community here in this worthwhile documentary), led us through the majority of this session.

Website for Red Semillas Libres Chile

For the larger network, visit Red de Semillas Libres de América